Loudness war : enough is enough !

24-bit high definition, 32-bit float, sampling rate from 44.1 to 192 kHz… whatever. We have never had such good technology to reproduce music and yet it all goes to waste if artists and recording labels believe we are too thick to hear the difference in sound quality or to understand the subtlety of harmonics, aeration and dynamics in a piece of music.

We’ve all bought an album only to be really disappointed when we listen to the completely bland recording with zero nuances. We’ve all stuffed the CD in the cupboard thinking “that’s 12 quids down the drain!”

The reason very often lies less with the mixing side of things (although this can happen) and more with the mastering process, a phase that consists in optimising how each instrument and voice is mixed, equalizing the frequencies and creating stereo spatiality while preserving the DYNAMICS. All the richness and depth of sound can be destroyed when the aim of mastering is to produce maximum volume, thereby sacrificing musicality to mass appeal.

(conclusion at the end)

This issue lies at the crux of the LOUDNESS WAR. It’s a steadily growing trend that verges on the alarming.

The root cause of the problem

At the outset, the practice was introduced to increase the impact of a piece of music when played over the radio, online (internet and streaming) or on portable players (car radios, iPods and smartphones). A souped-up single seems to sound better and louder than other recordings and so has a greater impact on the listener. While the effect is real at the time, making you think the sound is good, you quickly grow tired of listening to it and don’t feel any deep emotion.

What’s really absurd is that these media and players already use compression. And that means that both the dynamics and the musicality end up vanishing completely through over-compression, which produces a flat, featureless loudness with timbres drowned out in a “sludge” of sound and dampened percussion. Good dynamics, on the contrary, mean the whole musical unit is aerated and provides good spatial stereophonics where the notes are clearly defined and the harmonics respected.

If you think this problem only affects people with good HIFI systems, we invite you to don your headphones and listen to the short explanatory videos in this link. They will make you aware that “letting music breathe” concerns all of us.

For what purpose ?

So why does the music industry persist in using this process, which is destructive over the long term, and transforms often major works into throw-away sludge of little real value? After all, in the long run, a good album is also a well-recorded album.

You can hardly imagine the Beatles, not to mention Pink Floyd, both pioneers in their time who used compression intelligently, bowing down to the musical massacre we are witnessing today.

Does the industry want us to go back to vinyl records? It’s true that high dynamic compression is incompatible with this medium – which explains why the dynamic differentials are better respected. Yet if we go back to vinyl records, we’ll lose what current recordings do best – extremely precise reproductions that have more body than ever before. And this new audio quality is quite simply mind-blowing.

Which way out?

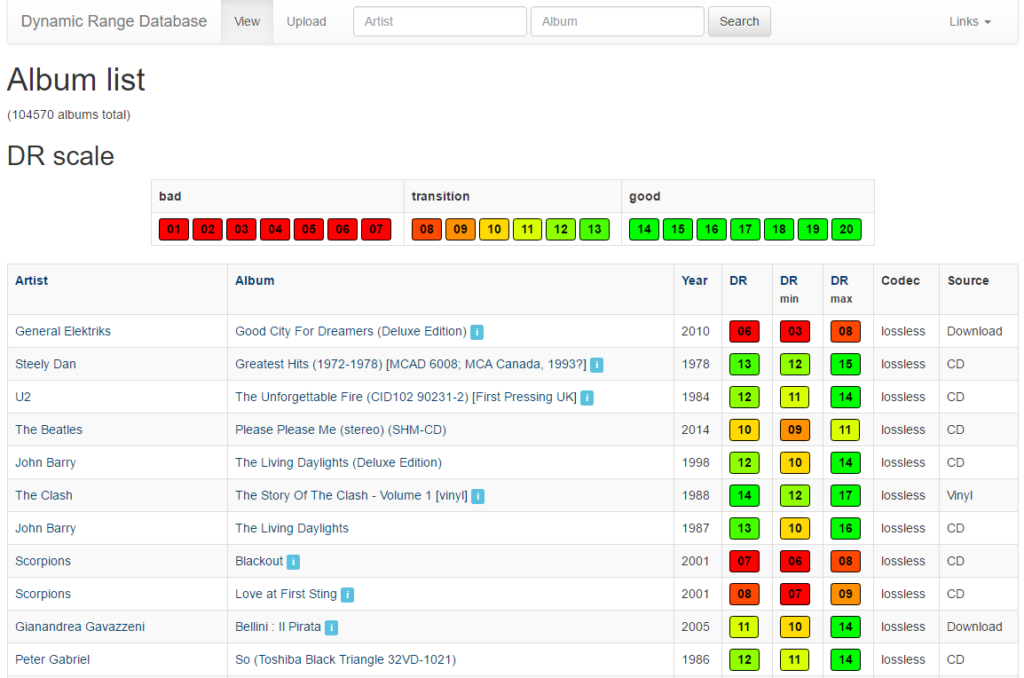

Whatever medium music is sold on, we would like to see the dynamic range indicated. Systematic DR labelling would act as a wake-up call for this fringe of the industry and tell them that we are not unaware of the decrease in recording quality. Moreover, the WHO has launched a health warning on this theme: with sounds constantly racked up to the maximum, the ear drum cannot relax – which is worse than heavy listening.

One solution would be for albums to be available in two formats. One for radio and the other for posterity. The arrival of 24-bit studio masters raises hopes that this quality format is readily available, but unfortunately current mastering is often carried out once and for all and then applied to all digital media – including high definition… So we end up stuffing the file in the cupboard and thinking “that’s 15 quids down the drain.”